Décio Pignatari se aproximou da sensação/ação/pensamento da poética de Maiakovski

Por Flávio Bittencourt Em: 04/12/2012, às 15H55

Por Flávio Bittencourt Em: 04/12/2012, às 15H55

[Flávio Bittencourt]

Décio Pignatari se aproximou da sensação/ação/pensamento da poética de Maiakovski

Ele foi um dos grandes.

Décio Pignatari tinha 85 anos e morreu de insuficiência respiratória (Jonas Oliveira/Folhapress)

(http://www.redebrasilatual.com.br/temas/entretenimento/2012/12/morte-de-decio-pignatari-deixa-vazio-nas-artes-e-na-academia)

Auguste Villiers de L'Isle-Adam

|

|

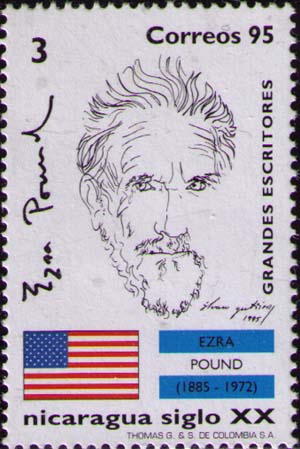

Nicaragua, 1995, 3 Cd. 14 (1/4) х 14. multicoloured Catalogues:

Plots: Pound Ezra Loomis

|

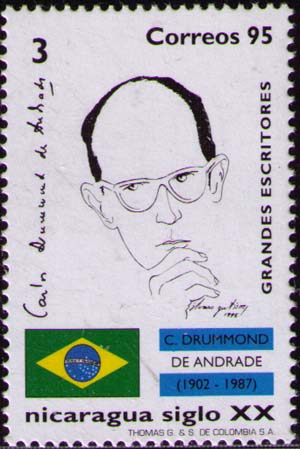

Nicaragua, 1995, 3 C. 14 (3/4) х 14. multicoloured

Catalogues:

Michel: 3601

Scott: 2134

Stanley Gibbons: MS3525f

Yvert et Tellier: 2135

Plots: Mayakovsky Vladimir

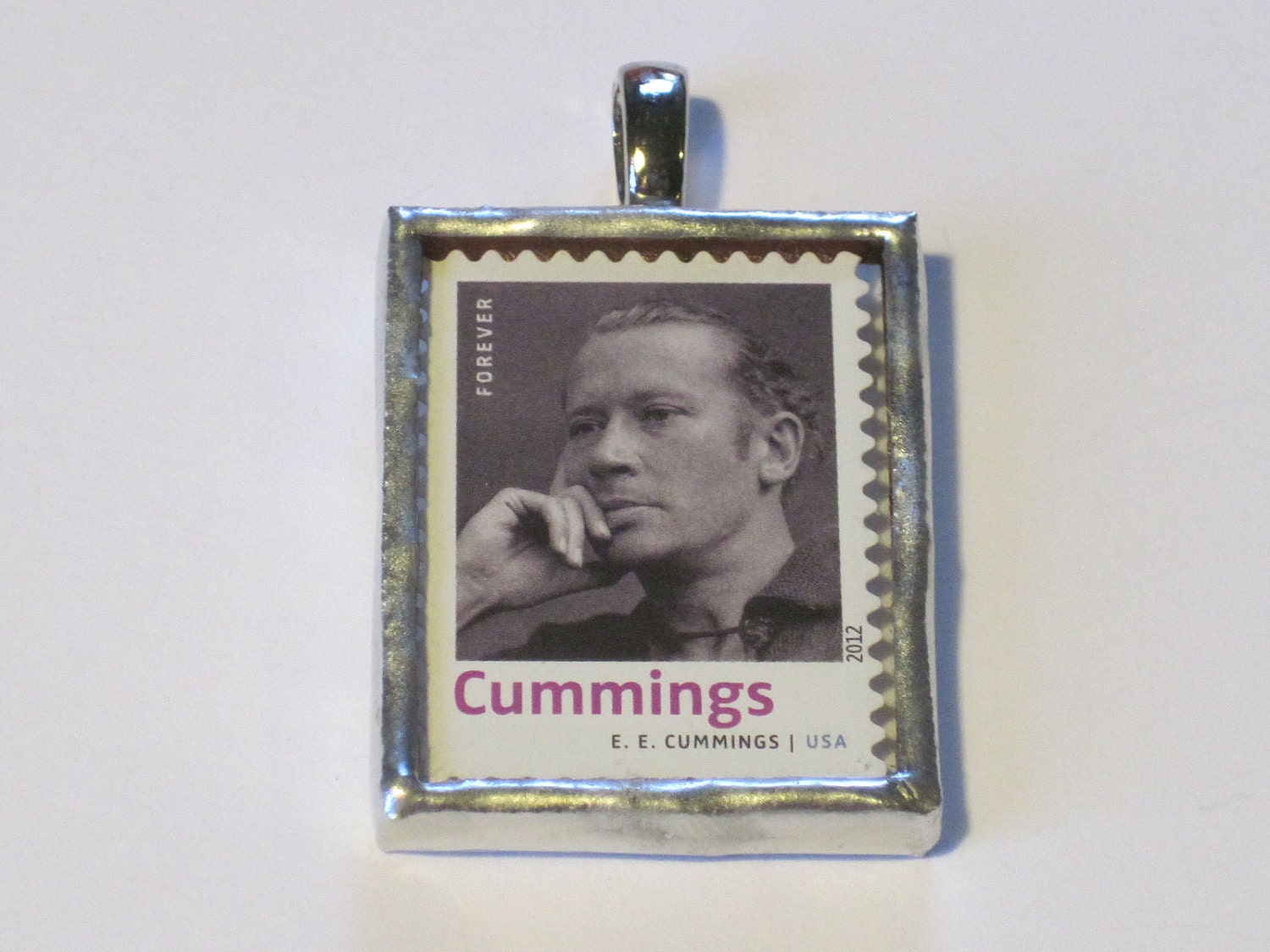

(http://www.etsy.com/listing/98580067/postage-stamp-pendant-e-e-cummings)

(http://www.domingocompoesia.com/2011/11/poesia-concreta.html)

4.12.2012 - Ele foi um dos grandes - Décio Pignatari (1927 - 2012), co-fundador do mundialmente importante movimento da poesia concreta. F. A. L. Bittencourt ([email protected])

"Ter , 04/12/2012 às 10:00

A luta poética de Décio Pignatari

Agência Estado

A morte do poeta Décio Pignatari, domingo, aos 85 anos, de infecção pulmonar, após longa convalescença, sofrendo do mal de Alzheimer, provoca um vazio na literatura brasileira, que ganhou com ele e os irmãos Augusto e Haroldo de Campos direito a ingresso no exclusivo grupo concreto internacional, não só no campo poético como visual e musical (durante os anos 1950 ele viveu na Europa, sendo próximo de artistas como o maestro Pierre Boulez). Grande momento da arte brasileira no século 20, o concretismo recebeu impulso enorme das criações literárias de Décio, cujos poemas visuais ajudaram a formatar a estética dos artistas do grupo Ruptura nos anos 1950, que forçaram a entrada do Brasil no campo da abstração pictórica.

Nascido em Jundiaí e formado pela Faculdade de Direito da USP, Décio começou sua carreira literária como poeta, em 1949, ao lado dos irmãos Campos, igualmente figuras fundamentais para o advento do concretismo no Brasil e presentes nos principais movimentos culturais dos anos 1950 em diante, inclusive no Tropicalista, nos anos 1960. No ano da realização da 1ª. Bienal Internacional de São Paulo, 1951, Décio rompeu com os poetas da geração de 1945 e fundou, no ano seguinte, o grupo Noigrandes com os irmãos Campos, dedicado à renovação da linguagem poética brasileira.

Décio teve um papel importante na divulgação da produção de poetas, romancistas e músicos da vanguarda europeia e americana, notadamente a do compositor John Cage. Esse livre trânsito entre as diversas artes sempre caracterizou a carreira do poeta, cujos interesses multidisciplinares o levaram a criar, por exemplo, poemas-cartazes no quarto número da revista Noigandres, em 1958, onde Pignatari apresentou seu plano-piloto para a poesia concreta brasileira, defendendo que não existe poesia revolucionária sem forma revolucionária, o que o aproximava do credo poético de Maiakovski.

Exercendo as mais diferentes funções nos anos 1960, de publicitário a cronista de futebol, Pignatari, que foi colaborador do jornal O Estado de S. Paulo, organizou happenings, performances e, nos anos 1970, tornou-se professor de Teoria Literária no curso de pós-graduação da USP, doutorando-se sob orientação do professor Antonio Candido. Além de diversos livros de poemas e traduções de Dante, Shakespeare e Marshall McLuhan, entre outros, Pignatari foi ensaísta ("Teoria da Poesia Concreta", 1965), contista ("O Rosto da Memória", 1988), romancista ("Panteros", 1992) e dramaturgo ("Céu de Lona", 2004). Seu poema mais conhecido é "Cloaca", musicado por Gilberto Mendes, que faz alusão ao mais popular refrigerante americano e termina com um arroto. Décio, que estava internado no Hospital Universitário da USP, foi enterrado nesta segunda-feira, no Cemitério do Morumbi. As informações são do jornal O Estado de S. Paulo."

(http://atarde.uol.com.br/cultura/materias/1470978-a-luta-poetica-de-decio-pignatari)

===

(http://lexilalia.blogspot.com.br/2012/04/speculative-modernism-i-villers-de.html)

===

REPÚBLICA DA NICARÁGUA

(SÉRIE DE SELOS POSTAIS HOMENAGEANDO

GRANDES ESCRITORES)

Nicaragua, 1995, 3 Cd. 14 (1/4) х 14. multicoloured

Catalogues:Michel: 3595

Scott: 2148a

Stanley Gibbons: MS3525

Yvert et Tellier: 2129

Plots: Drummond de Andrade Carlos

(http://www.philatelia.net/classik/stamps/?id=15351)

===

Mark Twain and Beyond: Literary Stamp Collecting

Yesterday was the United States Postal Service’s official release date for their new Mark Twain stamp, which got us to thinking about all the authors we’ve seen on stamps, whether on American or foreign postage. There are literally hundreds of these, of course — after all, what occasiondoesn’t call for a commemorative stamp? — but we’ve chosen some of our favorites here. Click through to see our collection of authors on stamps, and if you get inspired, head out to your local post office to buy a strip of Mark Twain postage and make your handwritten letters just that much more literary.

US-issued Mark Twain stamp, 2011

Irish-issued William Butler Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, Seamus Heaney and Samuel Beckett stamps, as part of a series commemorating Nobel laureates in literature. [via]

This stamp sheet from the former Soviet republic of Kyrgyzstan features Fulgencio Batista, Fidel Castro, Che Guevara, and Ava Gardner, not to mention Ernest Hemingway with his belly button showing. [via]

US-issued stamp of Henry David Thoreau [via]

US-issued stamp of Marianne Moore [via]

US-issued stamp of Edgar Allan Poe [via]

US-issued stamp of Edith Wharton [via]

Italian-issued Sir Francis Bacon Stamp [via]

Agatha Christie stamp, 2006. [via]

Denis Diderot stamp [via]

Swedish-issued Toni Morrison stamp, 1993. [via]

Swedish-issued Derek Walcott stamp, 1992. [via]

Czech Ernest Hemingway stamp. [via]

American Ernest Hemingway stamp. [via]

Monaco-issued Albert Camus stamp, 2007. [via]

Republic of Niger-issued Albert Camus stamp. [via]

German Hermann Hesse stamp, 1978. [via]

French-issued Charles Baudelaire stamp. [via]

US-issued Emily Dickinson stamp. [via]

US-issued Dr. Seuss stamp, 2004. [via]

US-issued Robert Frost stamp, 1974. [via]

Polish Nikolai Gogol stamp. [via]